|

|

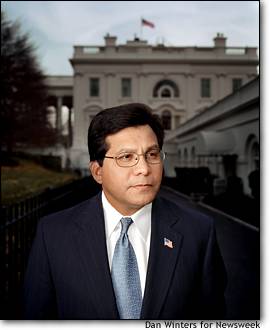

THE SOFT-SPOKEN

former Texas judge has been a powerful force behind many of the Bush

administration’s most aggressive—and controversial—tactics in the war on

terror. Whether it’s setting up military commissions or liberally

reinterpreting the laws on state-sponsored assassination, he has helped

Bush take a muscular approach. “In a time of crisis he’s going to make

sure the president has his full range of powers as commander in chief,”

says Timothy Flanigan, Gonzales’s former deputy. “That may mean pushing

the envelope on the law, without exceeding it.”.gif)

Director of

Special Projects, Alexis Gelber, joined us for a Live Talk to discuss

those selected and what's ahead in 2003. Read the transcript. Director of

Special Projects, Alexis Gelber, joined us for a Live Talk to discuss

those selected and what's ahead in 2003. Read the transcript.

.gif)

White House counsels

can usually stay out of the Washington crossfire. They’re not subject to

Senate confirmation, and they don’t have to wrestle the bureaucracy.

Instead, the president’s lawyer typically offers discreet advice on

legislation and helps the White House staff steer clear of ethical land

mines. In the months ahead, Gonzales will weigh in on a range of

politically charged legal issues—including Supreme Court cases on abortion

and affirmative action. But the 47-year-old lawyer may not be able to stay

below radar for long. Conventional wisdom in Washington is that two

Supreme Court justices—William Rehnquist and Sandra Day O’Connor—may

retire in the new year. And Gonzales is routinely mentioned as Bush’s

first choice to fill the next opening on the high court.

Gonzales has long been a Bush favorite. Friends say he passes

Bush’s all-important “good man” test: he is loyal, but not sycophantic. He

doesn’t grandstand. And he is able to reduce complicated issues to a

single sentence—a key attribute for a notoriously impatient president. The

men have history: a Texas native, Gonzales served as counsel to Bush when

he was governor. |

|

|

|

But it’s his

personal story that forms the emotional core of the relationship. The son

of migrant workers, Gonzales grew up in a house without running water and

was the first in his family to go to college. After Harvard Law, he became

the first minority partner at Vinson & Elkins, a posh Houston firm,

and eventually made it to the Texas Supreme Court. For Bush, Gonzales is a

resonant American symbol—a Hispanic who rose from poverty to a president’s

side. Placing him on the Supreme Court could help Bush with a key

political goal: attracting Hispanic and other minority voters to the

Republican Party.

A corporate lawyer most

of his career, Gonzales hasn’t left a long paper trail to scrutinize. So

far, liberals seem cautiously optimistic that he would be a moderate they

could live with. But some conservatives have quietly questioned his

ideological credentials—in a Texas abortion case, he voted to allow a

teenage girl to bypass a parental-notification law. Interviewed in his

corner White House office, he wouldn’t acknowledge that he’s a candidate

for the court. But in the same breath, he seemed eager to send a message

to anyone trying to divine his position on abortion. “It wasn’t a

constitutional issue,” he said, of the Texas case. “It was purely a

statutory interpretation question.”

Gonzales will face other tough questions. Some, even inside the

administration, ask whether he has the intellectual depth—and passion for

arcane legal issues—for the job. One administration official familiar with

his record describes his judicial opinions as “workmanlike but not

incisive.” Lately, some Bushies have been quietly floating another

possible spot for him instead: attorney general. Whatever job he gets,

Alberto Gonzales may soon be a household name. |

|